#StudiousSaturday: 6 Times John Cage Redefined Vocal Virtuosity

#StudiousSaturday: 6 Times John Cage Redefined Vocal Virtuosity

This week's #StudiousSaturday brings you 6 Times John Cage Redefined Vocal Virtuosity. Written by Justin Friello

by Justin Friello

The American composer John Cage (1912-1992) is often known for his unconventional approach to composition, having repeatedly questioned traditional notions of music-making and performance. As a result, a common critique of his work is that it requires little to no skill to perform, or that anyone could have composed it [1,2]. In practice, however, this is not always the case. There are times when Cage calls for a virtuosic performer, though one must reexamine and redefine the principles of virtuosity in order to come to this conclusion. Here are six works in which Cage redefined the term.

Starting right with his performance instructions, Cage lets the vocalist know that a certain type of performance style will lead to virtuosity: "A virtuoso performance will include a wide variety of styles of singing and vocal production." [3] Whereas, traditionally, virtuosity is a subjective description often applied to a performance following its completion, Cage makes virtuosity an inherent parameter of the work, and even gives instructions on how to achieve it. In this sense, virtuosity is made objective and attainable by all. Cage further eases the process of achieving virtuosity by including descriptions of four explicit and identifiable singing styles in the performance notes. Three of these are worth exploring in detail.

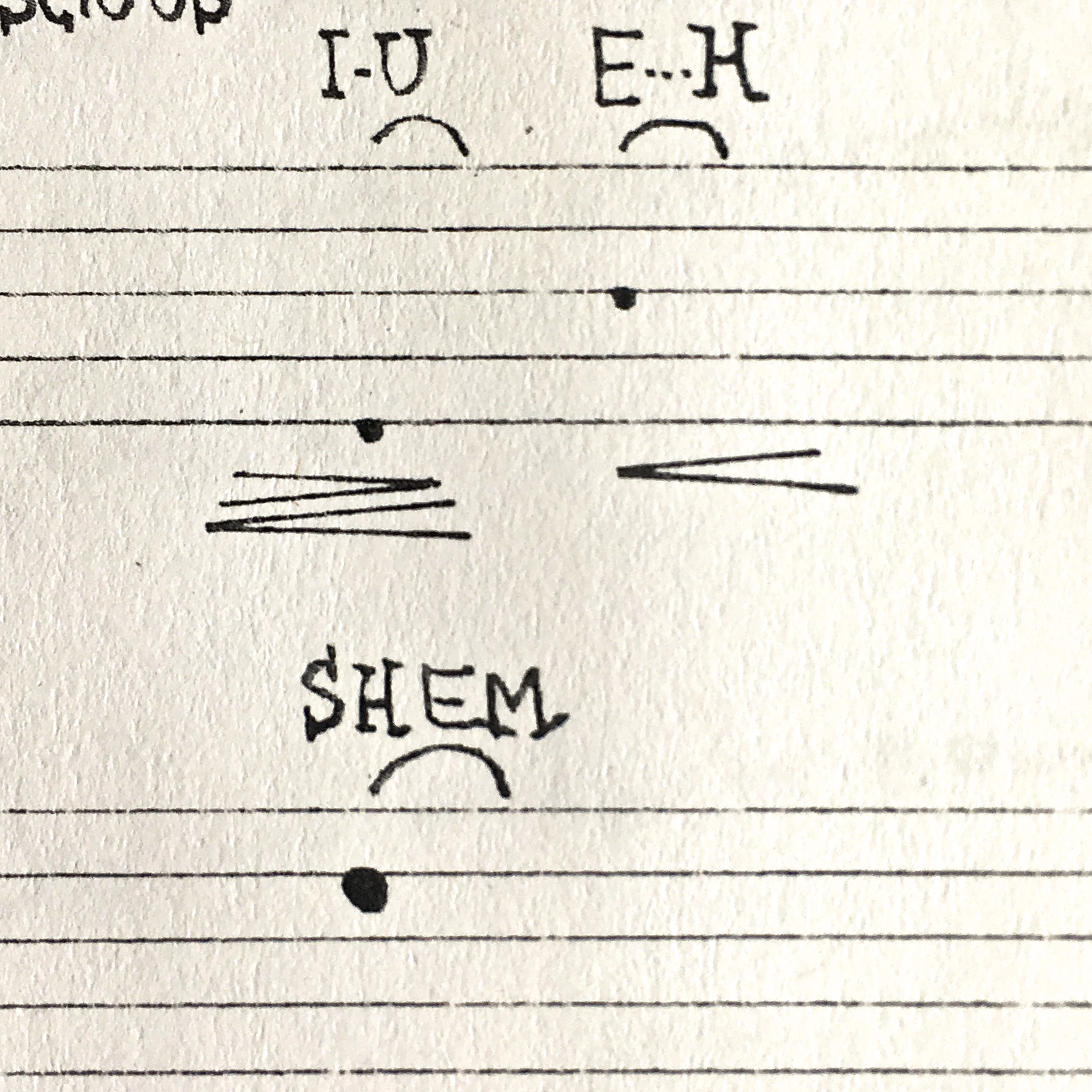

The first of these techniques is microtonal singing. Cage writes: "The lines of staves are far-apart. Where notes are not centered in the space or on the line, they suggest microtonal alterations." [4]

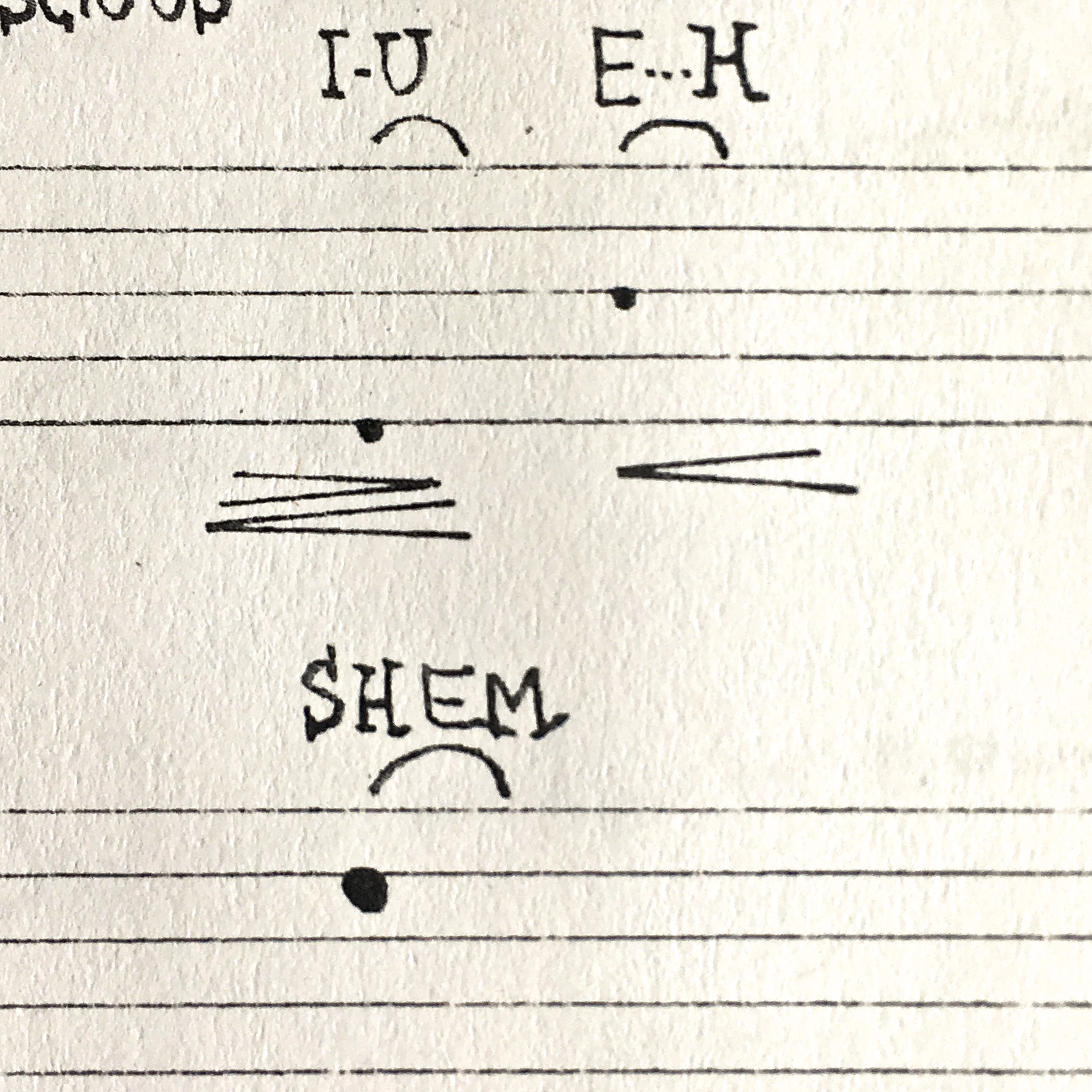

Each of the three note-heads shown here fall just below the staff lines, indicating an indeterminate flattening of pitch relative to the spacing of adjacent note-heads. "I-U" and "E···H" sit completely below the line, where "SHEM" creeps slightly onto the line. One could, therefore, (though there is no clef shown) sing the former two as D-quarter-flat and B-quarter-flat, respectively, and the latter as D-sixth-flat. Doing this, of course, take a tremendous amount of vocal control and muscle-memory to locate these pitches without sliding into them.

The second technique is the vocalization of sprechstimme and simple speech. Again, Cage clarifies this technique in two of his instructions: 1) "Sprechstimme may be used where the text has some length", and 2) (where semicircles appear in different positions above note-heads): "…pitch given is to be sung at some point after the phrase beginning and some point before the phrase ending…the pitch given is to be the end of the phrase…[or] pitch given is to begin the phrase." [5] In each case, speech is combined with singing. This expands the definition of what constitutes music in a vocal piece. Though sprechstimme was and is a widely used vocal technique, the alternation of speech and singing within a single phrase is novel and adds to the virtuosity of the performance.

Cage piles on the unconventionality with a third technique, "noises…produced vocally", notated with note-heads far below the staff. [6]

The insertion (or interruption) of singing by noise is a theme that runs throughout Cage's music (see: Aria below). In Solo for Voice 1, Cage combines these noises with text such that the vocalist has complete freedom in choosing the timbre of these sounds, but is limited to those which can still retain a semblance of the text provided. These decisions, made and implemented by the performer, increase the level of virtuosity needed in order to perform this work.

One12 is an odd little piece, one that was only published after Cage's death. The work's notation is:

Furthermore, the musical material is varied, creating a certain level of interest for the singer. In this work, however, Cage requires the performer to focus on a single task for an unspecified length of time. 20 minutes is somewhat lengthy, but a given performance could last an hour or two, or entire day if desired. For a vocalist, this presents the challenge of keeping attentiveness to the work without losing the improvisatory nature (never mind the vocal strain). Cage's statement on virtuosity in Solo For Voice 1 can be applied similarly to this work, though one might replace the varied styles of singing in that work with the varied linguistic content in One12.

A virtuosic performance requires a performer to remember the words, syllables, and sounds he's previously made and continually vary them spontaneously. And if a performance was virtuosic on one occasion, it would be up to that performer to radically alter the linguistic content in subsequent performances, else he risk copying himself. On top of all that, the performer is required not to get tongue-tied. After 10 minutes or more of staring at a page of numbers, one imagines it wouldn't be hard to suddenly make the wrong sound or even stutter. [8] All of these obligations to the work is what makes any correct performance of One12 virtuosic.

Cage clarifies the performance practice for the work thusly:

"These type face and size differences may be used to suggest an improvised vocal line having any changes of intensity, quality, style, etc., not following any conventional rule. The words and syllables are not to be made clear: rather, attention is given to each letter (though not separating it from the letter that follows; a given letter may be vocalized in many ways; do not search to establish any pronunciation rule." [10]

Here, again, we have a piece where spontaneity is encouraged, but must be closely self-monitored to ensure that a performer's subconscious does revert his performance practice back to what she may have learned in school; in this work, patterns and repetition are not important, in fact, they're discouraged. Much like One12, what matters is an intuitive and primal response to the visual stimuli of the score and the ability to translate that into a vocal performance with a clarity of intention.

Cage suggests that a performance of this work feature at least 5 of the mesostics, though a presentation of all of them would fill an evening-length program of "one and one-half to three hours." [11] Again, one can imagine the physiological support needed to carry the voice through three hours of non-stop improvisation. Truly virtuosic.

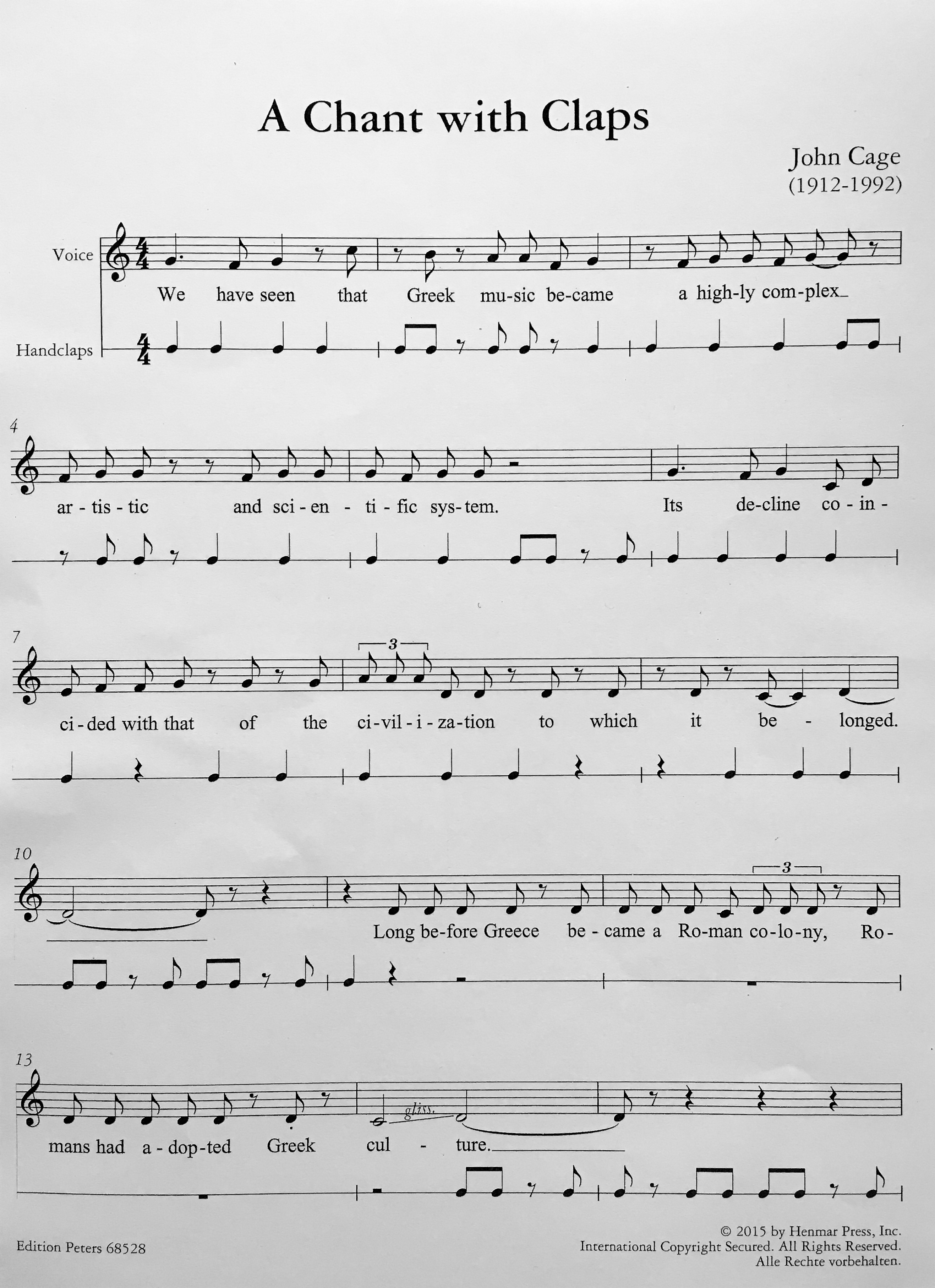

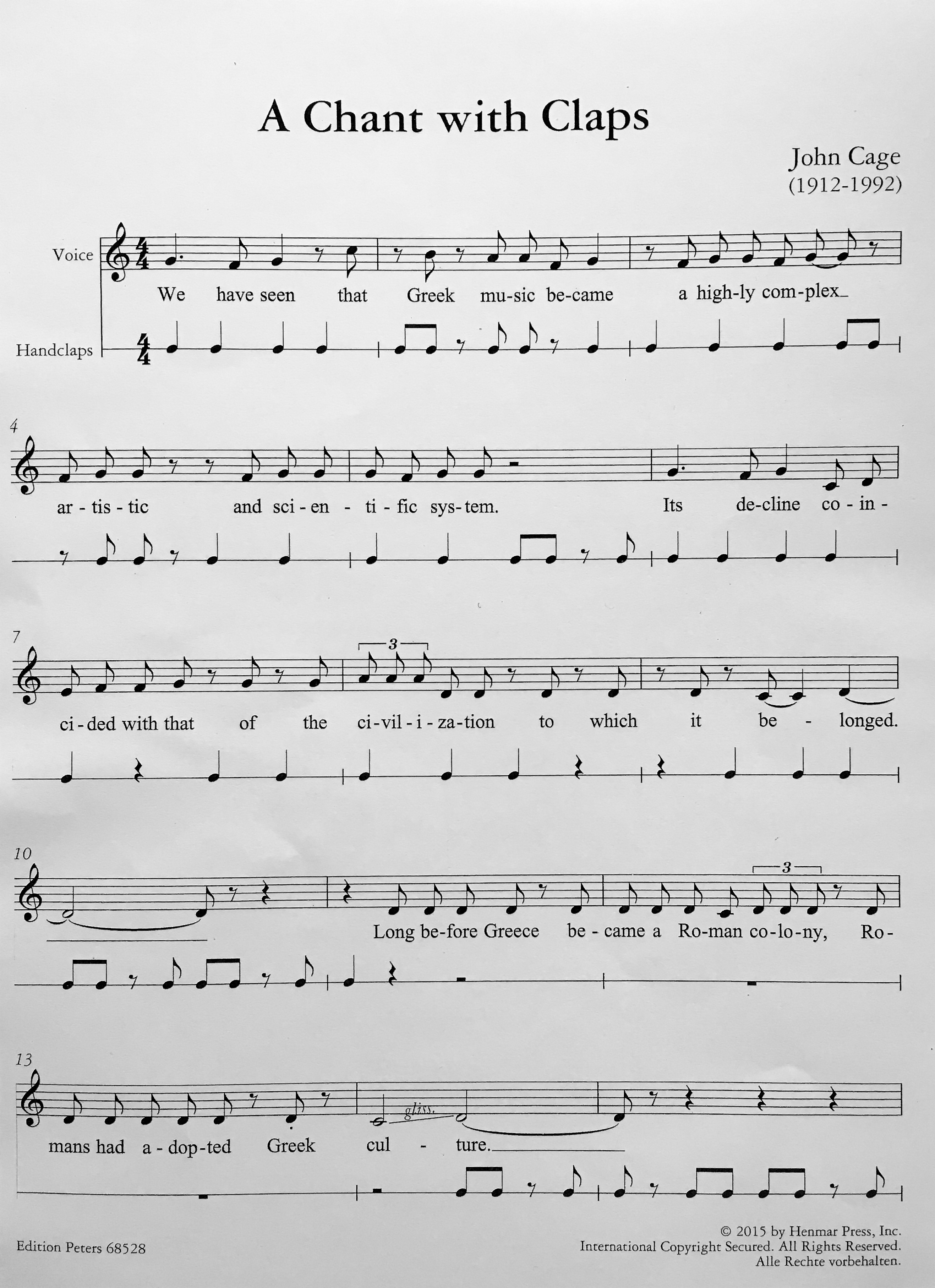

A Chant With Claps is a piece for solo performer in which a vocalist provides his own accompaniment. Unlike a singer-songwriter who accompanies his own singing by playing a guitar or piano part which supports and plays off of the vocal line, in this work, Cage asks the performer to clap his hands in rhythms which do not only not repeat, but which, at times, create a sense of meter contrary to that of the vocal line. It's difficult enough that the vocal line, though written in 4/4, suggests meters other than common time, but add to that the task of clapping in a similarly tricky fashion and you've got a real challenge on your hands. [12,13]

What Cage is calling for here is a bifurcation of focus. Note that he does not ask for a refined vocal technique. [14,15] He is only interested in the relationship between two elements of the body over both of which the performer must have complete control. In this way, Cage redefines vocal virtuosity as the ability to carry out vocal practices while also performing other tasks. [16] And it's not enough to go on auto-pilot for one or the other. The rhythms of both are not connected, nor are they repetitive enough to focus primarily on one or the other; attention must be paid to both equally.

Further complicating the matter is the possible pitch-range of the piece. Cage states: "The notation represents…time vertically, roughly suggested rather than accurately described." [24] If we're assuming the height of the page represents the range of a person's voice stretched to its extremes, then this notation:

It means that the singer needs complete control over her voice to jump from register to register the way Cage intended. This is closer to the classic notion of virtuosity, although Cage milks it for all it's worth.

Finally, it's worth mentioning that Cage, like in Solo for Voice 1, wants the singer to create noises through " 'unmusical' use of the voice". [25] This is represented in the score by black squares which dot the bottom of the page:

Though Cage also allows for these sounds to be made using percussion or mechanical or electronic devices [26], if we assume a performer uses only her voice, then quick transitions between vocal styles are made even more difficult because of the taxing vocal techniques a performer may use to be as unmusical as possible. [27]

In any given performance of Song Books, a singer many perform many of these pieces back to back, requiring the ability to turn on and off each of these techniques; virtuosity, indeed.

What's more is that in many of these pieces, the singer is accompanied by electronics which manipulate the singer's voice. Take, for example, Solo for Voice 46:

A straightforward melody is complicated by changes in amplification volume and electronic modulation of an indeterminate parameter at points marked with the letters "A" and "M" in circles, respectively. The bottom system displays a tricky melody. Now imagine having to sing that while listening to the playback of yourself modified in some way, let's say a delay effect. You'd be singing harmony with yourself, and not even necessarily in time. Or let's say the amplitude was increased to a deafening level by the person controlling the electronics (assuming someone else was performing this with you, as is often the case) and you couldn't hear yourself anymore, but still had to sing the piece. The level of muscle memory required to perform the piece and not sound like a screaming concert-goer would be astounding. For all these reasons, Song Books is the quintessential piece in Cage's redefining of virtuosity.

1 See: 4′33″.

2 And as a premature retort: You didn't, and no, you couldn't have.

3 Cage, John, Solo For Voice 1 (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1960), 3.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 "One12," John Cage Complete Works. Accessed May 8, 2017. http://johncage.org/pp/John-Cage-Work-Detail.cfm?w...

8 And from my own experience making the above video, I can confirm how difficult it is to maintain clarity and precision under the circumstances.

9 Cage, John, Sixty-two Mesostics re Merce Cunningham (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1971).

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 The piece is quite difficult to perform, and if you don't believe me, give it a shot. Note how the vocalist in the video above holds out the D in measure 15 for longer than notated. But I won't nitpick here. (Though, if you're going to record a whole album of Cage works, you might as well perform them correctly.)

13 Oh, and yes, pun intended.

14 In fact, much of Cage's vocal work calls attention to the materials themselves rather than the voices producing them. Remember that Cage, a follower of Zen Buddhist practices, wanted to remove the ego from his music on two fronts: his own from his compositions and that of the performers from their realizations of his work.

15 Nor does he ask for a refined hand-clapping technique. And if someone could show me what that is, I'd be most interested.

16 In a sense, that's what a lot of modern musical-theatre and operatic performance practice is. Consider the performers' ability to hit their blocking, act, and dance, all while singing perfectly. In the case of ACWC, this notion has been boiled down to two simple actions: singing and clapping.

17 Cage, John, Sixty-two Mesostics re Merce Cunningham (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1971).

18 Cage, John, Aria (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1960).

19 Italian, French, and English being standard languages in the vocal repertoire.

20 "Aria," John Cage Complete Works. Accessed May 8, 2017. http://johncage.org/pp/John-Cage-Work-

Detail.cfm?work_ID=29

21 It was 1959; forgive her.

22 Cage, John, Aria.

23 In my first performance of the piece in 2008, I chose the following vocal styles: panicked (with whispering); Maya Rudolph impersonating Donatella Versace; a very nasal, high-pitched boy; an excited Italian immigrant; idle boat motor; forte operatic; perfect and calm over-enunciation; legato martial arts commands; slurred and airy folk singing; and Scooby Doo's voice cracking.

24 Cage, John, Aria (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1960).

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 In my second realization of this piece in 2011, I chose the following sounds/actions through chance operations: two metal pots banging like cymbals, a scream, applause, induce vomiting, short crying sound, laughter, throw a tennis ball against the ground, sit down (perform the rest of the piece from the ground), gunshot (cap gun), crack a piece of wood, run offstage and reappear on the opposite side, take off all clothing, exhale audibly, and "Bzzzzz".

28 Cage, John, Song Books, Volumes I & II (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1970).

* * *

Justin Friello is a singer/actor/composer/multi-instrumentalist from Schenectady, NY. Since 2006, he has been writing text settings for each of E. E. Cummings' published poems. Thus far, he's written close to 300 works for a variety of ensembles featuring voice. Justin is also a singer-songwriter whose most recent solo album, Jack & Jill, was released in August 2016. For more information and recordings, visit: justinfriello.com, justinfriello.bandcamp.com, facebook.com/justinfriellomusic, and youtube.com/justinfriello.

Make sure to subscribe to the FloVoice Newsletter to never miss a note!

The American composer John Cage (1912-1992) is often known for his unconventional approach to composition, having repeatedly questioned traditional notions of music-making and performance. As a result, a common critique of his work is that it requires little to no skill to perform, or that anyone could have composed it [1,2]. In practice, however, this is not always the case. There are times when Cage calls for a virtuosic performer, though one must reexamine and redefine the principles of virtuosity in order to come to this conclusion. Here are six works in which Cage redefined the term.

1. Solo For Voice 1 (1958)

Starting right with his performance instructions, Cage lets the vocalist know that a certain type of performance style will lead to virtuosity: "A virtuoso performance will include a wide variety of styles of singing and vocal production." [3] Whereas, traditionally, virtuosity is a subjective description often applied to a performance following its completion, Cage makes virtuosity an inherent parameter of the work, and even gives instructions on how to achieve it. In this sense, virtuosity is made objective and attainable by all. Cage further eases the process of achieving virtuosity by including descriptions of four explicit and identifiable singing styles in the performance notes. Three of these are worth exploring in detail.

The first of these techniques is microtonal singing. Cage writes: "The lines of staves are far-apart. Where notes are not centered in the space or on the line, they suggest microtonal alterations." [4]

Solo for Voice 1, p. 1

Each of the three note-heads shown here fall just below the staff lines, indicating an indeterminate flattening of pitch relative to the spacing of adjacent note-heads. "I-U" and "E···H" sit completely below the line, where "SHEM" creeps slightly onto the line. One could, therefore, (though there is no clef shown) sing the former two as D-quarter-flat and B-quarter-flat, respectively, and the latter as D-sixth-flat. Doing this, of course, take a tremendous amount of vocal control and muscle-memory to locate these pitches without sliding into them.

The second technique is the vocalization of sprechstimme and simple speech. Again, Cage clarifies this technique in two of his instructions: 1) "Sprechstimme may be used where the text has some length", and 2) (where semicircles appear in different positions above note-heads): "…pitch given is to be sung at some point after the phrase beginning and some point before the phrase ending…the pitch given is to be the end of the phrase…[or] pitch given is to begin the phrase." [5] In each case, speech is combined with singing. This expands the definition of what constitutes music in a vocal piece. Though sprechstimme was and is a widely used vocal technique, the alternation of speech and singing within a single phrase is novel and adds to the virtuosity of the performance.

Cage piles on the unconventionality with a third technique, "noises…produced vocally", notated with note-heads far below the staff. [6]

Solo for Voice 1, p. 1

The insertion (or interruption) of singing by noise is a theme that runs throughout Cage's music (see: Aria below). In Solo for Voice 1, Cage combines these noises with text such that the vocalist has complete freedom in choosing the timbre of these sounds, but is limited to those which can still retain a semblance of the text provided. These decisions, made and implemented by the performer, increase the level of virtuosity needed in order to perform this work.

2. One12 (1992)

video by Justin FrielloOne12 is an odd little piece, one that was only published after Cage's death. The work's notation is:

"[a] single-page holograph indicat[ing] that the performer prepare a score consisting of 640 random numbers between 1 and 12. For each number "1", the performer speaks an "empty" (non-substantive) word; each "12" corresponds to a "full" word (noun, adjective, etc.). For numbers "2-11", the performer produces a phonemic sound drawn from the word for the number, e.g. "t" or "too" for 2." [7]The performance is completely improvisatory, which, given the instructions, requires a high level of concentration and stamina. My own performance (included above), lasts just over 20 minutes. Often, we think of virtuosity as being linked to a high-degree of technical caliber. We watch opera and understand the level of craft that a singer has put into a performance based on accepted notions of proper vocal technique. What is often not considered is the duration of a performance. Opera often lasts 3 hours or more, though any one singer is usually not on stage for the entire interval, and there's often an included intermission.

Furthermore, the musical material is varied, creating a certain level of interest for the singer. In this work, however, Cage requires the performer to focus on a single task for an unspecified length of time. 20 minutes is somewhat lengthy, but a given performance could last an hour or two, or entire day if desired. For a vocalist, this presents the challenge of keeping attentiveness to the work without losing the improvisatory nature (never mind the vocal strain). Cage's statement on virtuosity in Solo For Voice 1 can be applied similarly to this work, though one might replace the varied styles of singing in that work with the varied linguistic content in One12.

A virtuosic performance requires a performer to remember the words, syllables, and sounds he's previously made and continually vary them spontaneously. And if a performance was virtuosic on one occasion, it would be up to that performer to radically alter the linguistic content in subsequent performances, else he risk copying himself. On top of all that, the performer is required not to get tongue-tied. After 10 minutes or more of staring at a page of numbers, one imagines it wouldn't be hard to suddenly make the wrong sound or even stutter. [8] All of these obligations to the work is what makes any correct performance of One12 virtuosic.

3. Sixty-two Mesostics re Merce Cunningham (1971)

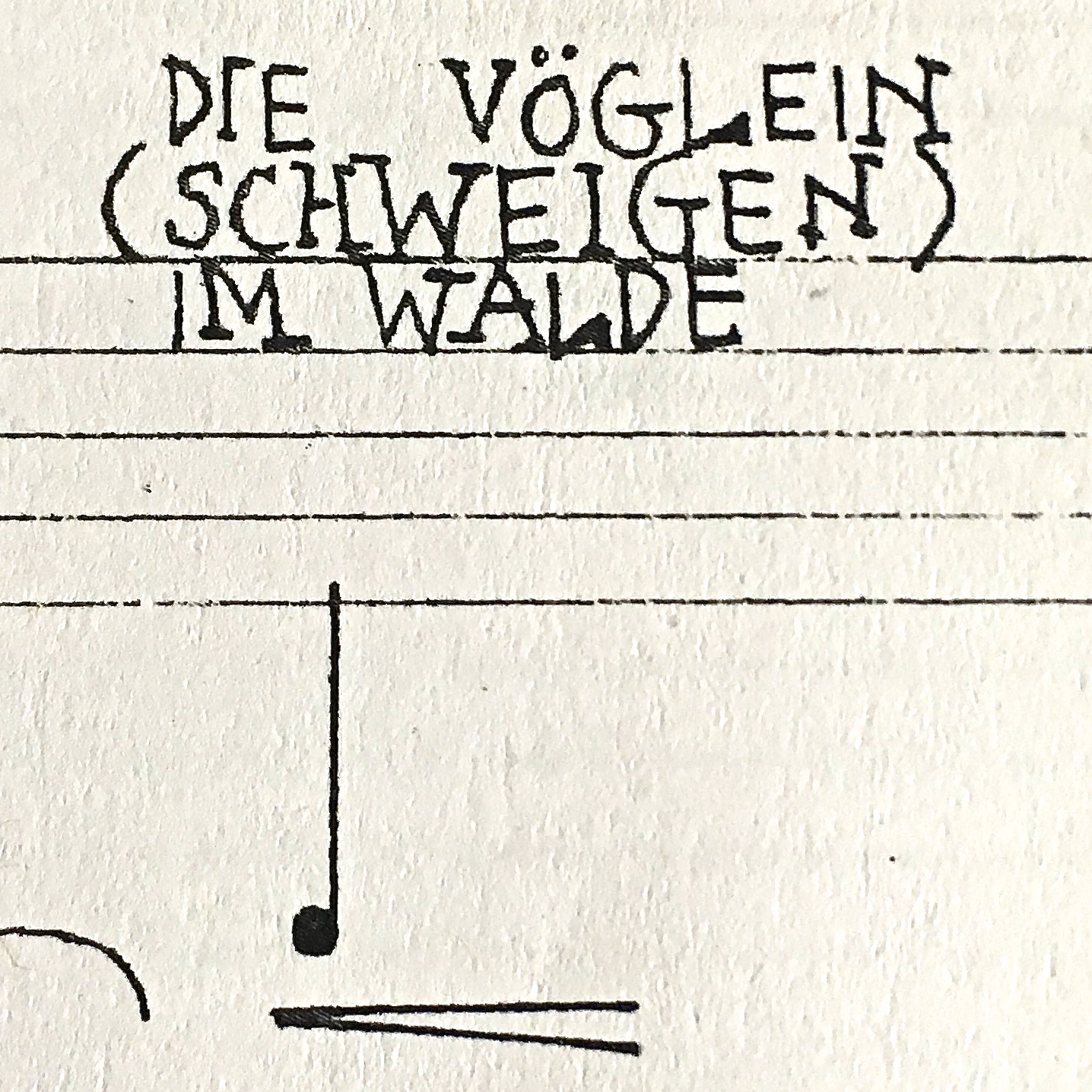

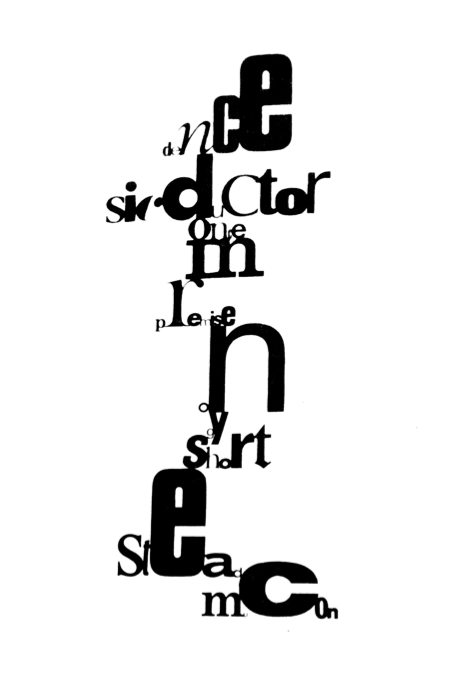

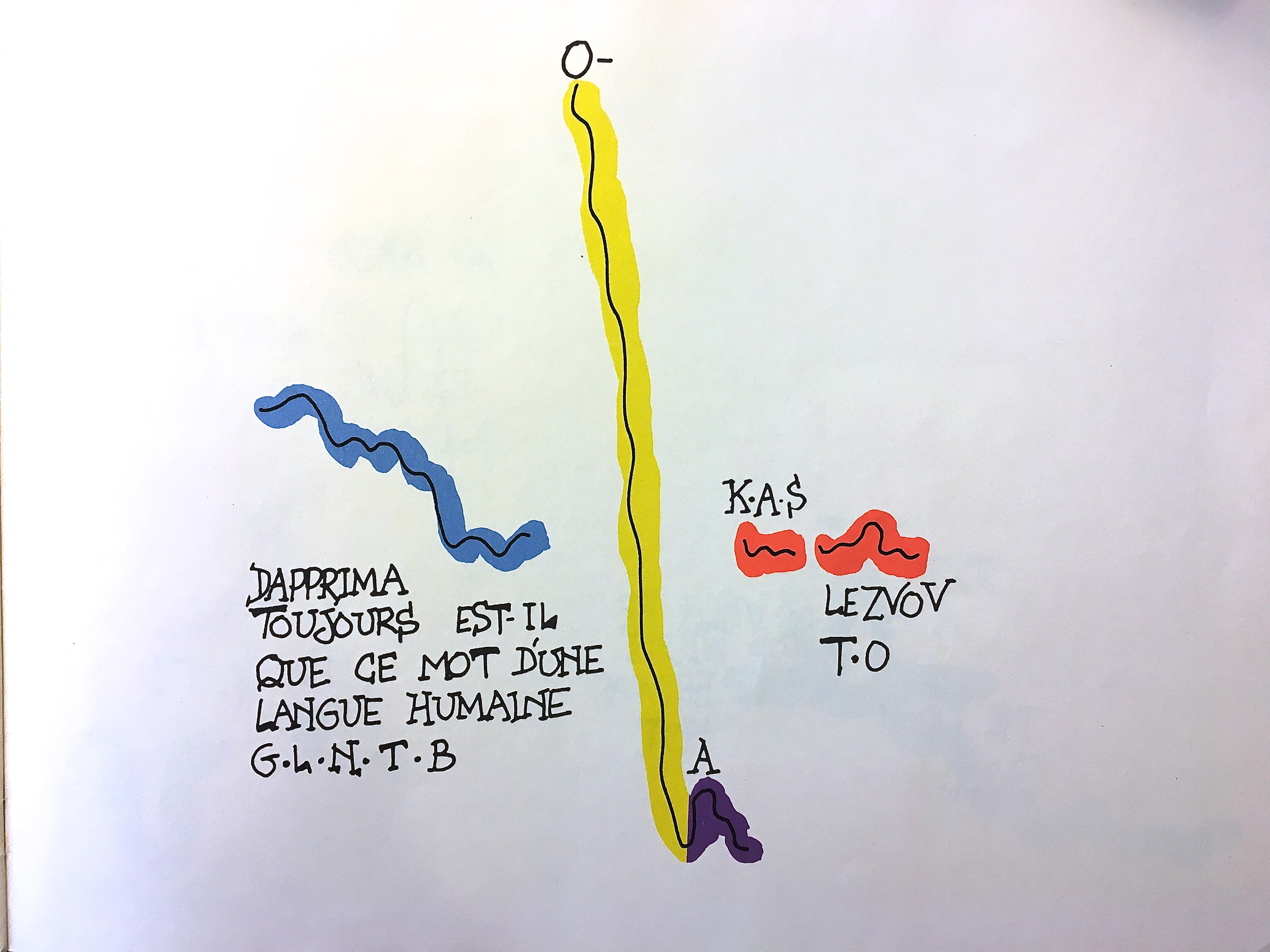

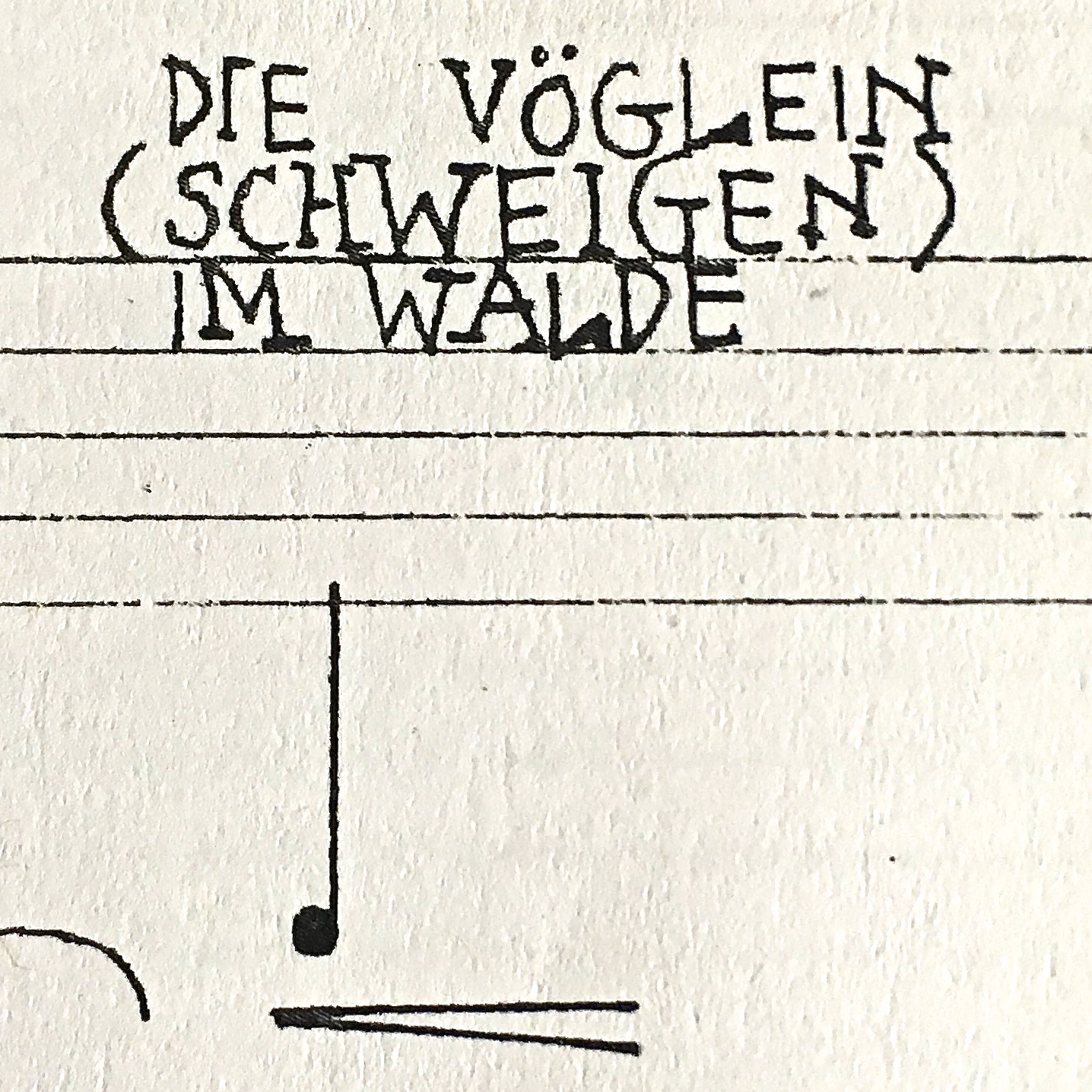

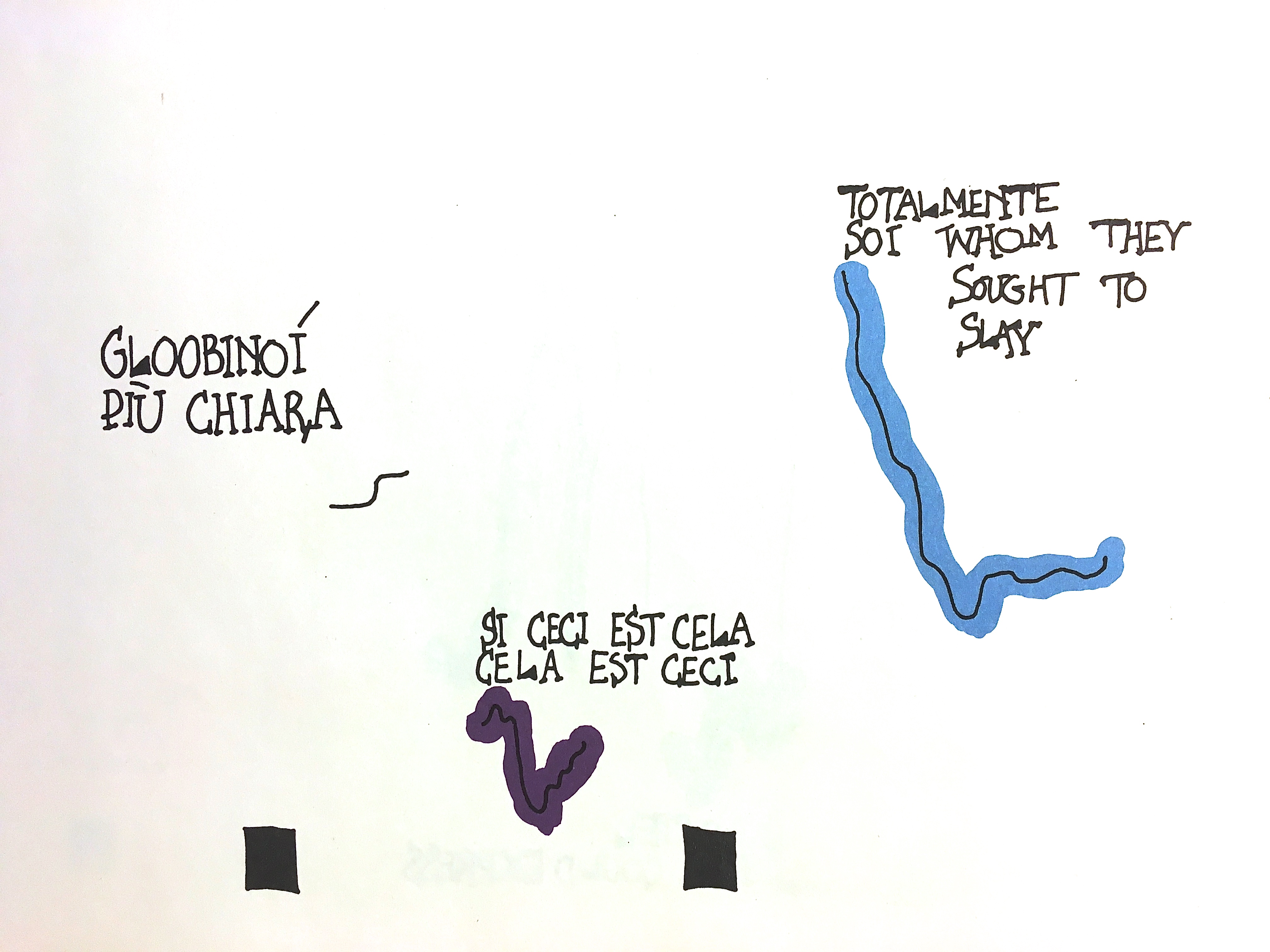

Riding the same virtuosic rails as One12, a Sixty-two Mesostics amplifies the ideas of stamina and improvisation, taking them to extremes. The score for the work consists of sixty-two mesostic poems, one per page, with their typographic elements altered to vary the size and font of each word, syllable, and letter, using "a gamut of about seven hundred and thirty different type faces or sizes." [9]Sixty-two Mesostics re Merce Cunningham, p. 1

Cage clarifies the performance practice for the work thusly:

"These type face and size differences may be used to suggest an improvised vocal line having any changes of intensity, quality, style, etc., not following any conventional rule. The words and syllables are not to be made clear: rather, attention is given to each letter (though not separating it from the letter that follows; a given letter may be vocalized in many ways; do not search to establish any pronunciation rule." [10]

Sixty-two Mesostics re Merce Cunningham (1971)

Here, again, we have a piece where spontaneity is encouraged, but must be closely self-monitored to ensure that a performer's subconscious does revert his performance practice back to what she may have learned in school; in this work, patterns and repetition are not important, in fact, they're discouraged. Much like One12, what matters is an intuitive and primal response to the visual stimuli of the score and the ability to translate that into a vocal performance with a clarity of intention.

Cage suggests that a performance of this work feature at least 5 of the mesostics, though a presentation of all of them would fill an evening-length program of "one and one-half to three hours." [11] Again, one can imagine the physiological support needed to carry the voice through three hours of non-stop improvisation. Truly virtuosic.

4. A Chant With Claps (1940)

A Chant With Claps is a piece for solo performer in which a vocalist provides his own accompaniment. Unlike a singer-songwriter who accompanies his own singing by playing a guitar or piano part which supports and plays off of the vocal line, in this work, Cage asks the performer to clap his hands in rhythms which do not only not repeat, but which, at times, create a sense of meter contrary to that of the vocal line. It's difficult enough that the vocal line, though written in 4/4, suggests meters other than common time, but add to that the task of clapping in a similarly tricky fashion and you've got a real challenge on your hands. [12,13]

A Chant With Claps, p. 1

What Cage is calling for here is a bifurcation of focus. Note that he does not ask for a refined vocal technique. [14,15] He is only interested in the relationship between two elements of the body over both of which the performer must have complete control. In this way, Cage redefines vocal virtuosity as the ability to carry out vocal practices while also performing other tasks. [16] And it's not enough to go on auto-pilot for one or the other. The rhythms of both are not connected, nor are they repetitive enough to focus primarily on one or the other; attention must be paid to both equally.

5. Aria (1958)

Aria, a work of chaos and whimsy, exemplifies Cage's redefinition of vocal virtuosity and the role of speech in vocal music. It is actually in his introduction to Sixty-two Mesostics that his justification for why speech is music can be found:Speaking without syntax, we notice that cadence, Dublinese or ministerial, takes over.…To raise language's temperature we not only remove syntax: we give each letter undivided attention…to read becomes the verb to sing. [17]And thus, speech is elevated to meaningful musical sound. Cage explodes this idea in 1958's Aria by requiring the singer perform a number of verbal exercises: 1) Cage writes in the performance notes: "The text employs vowels and consonants and words from 5 languages: Armenian, Russian, Italian, French, and English." [18] As any vocal student will tell you, learning foreign diction is an essential part of the craft. Here, Cage twists that idea, assuming that a singer doesn't speak a lick of Armenian or Russian, [19] and asks him to speak it here, but in any of the eight vocal styles the performer himself chooses. That's right, the score is colored in ten different ways with each color corresponding to a different vocal style. Cathy Berberian, who premiered the piece in 1959 [20], chose the following styles: Jazz, Contralto, Sprechstimme, Dramatic, Marlene Dietrich, Coloratura (and Coloratura Lyric), Folk, Oriental [21], Baby, and Nasal. [22] Looking back to what Cage said in the instructions for Solo for Voice 1, every performance of Aria is guaranteed to be virtuosic, provided that the singer chooses disparate vocal styles. [23]

"Aria" performed by Justin Friello

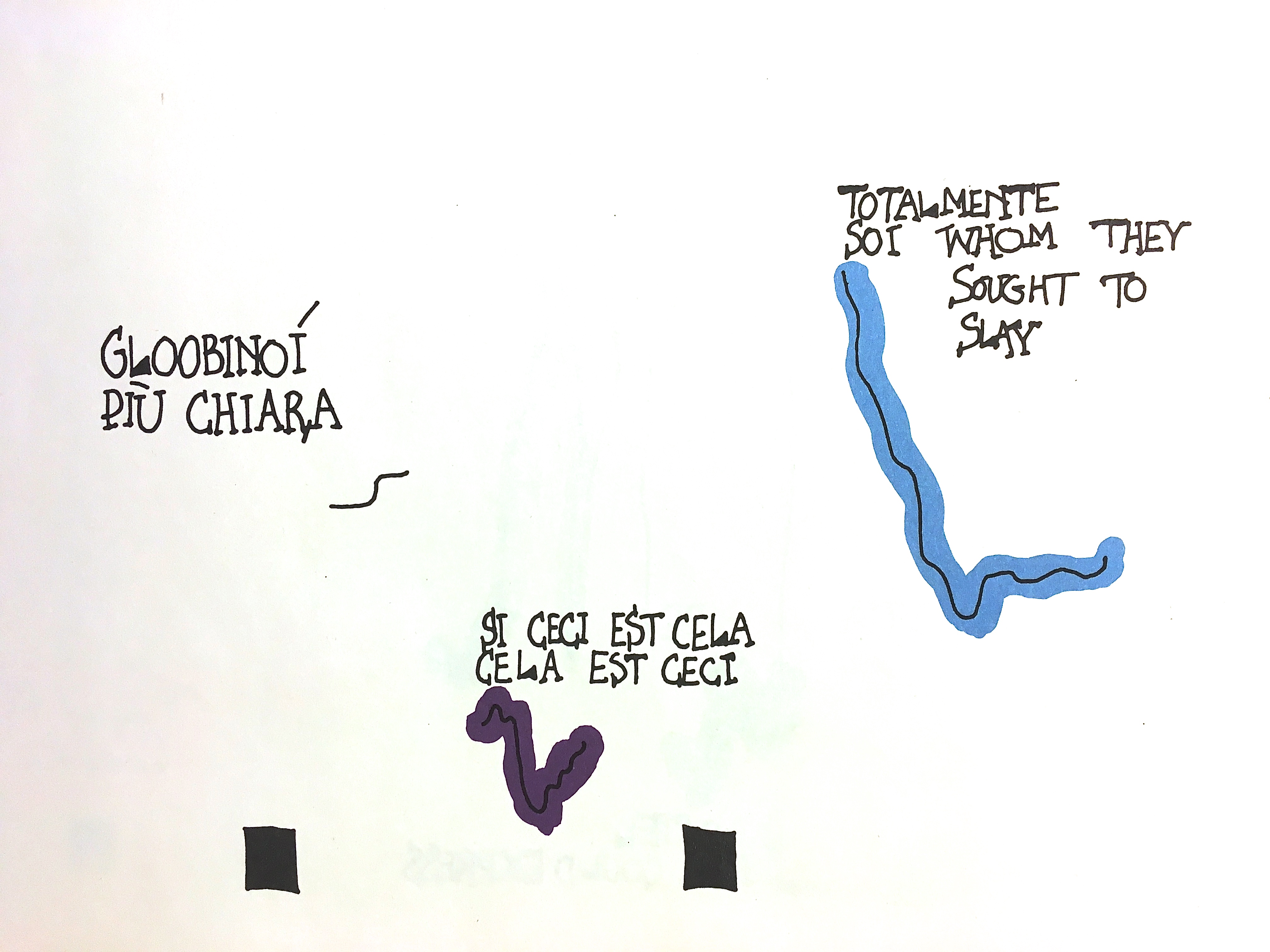

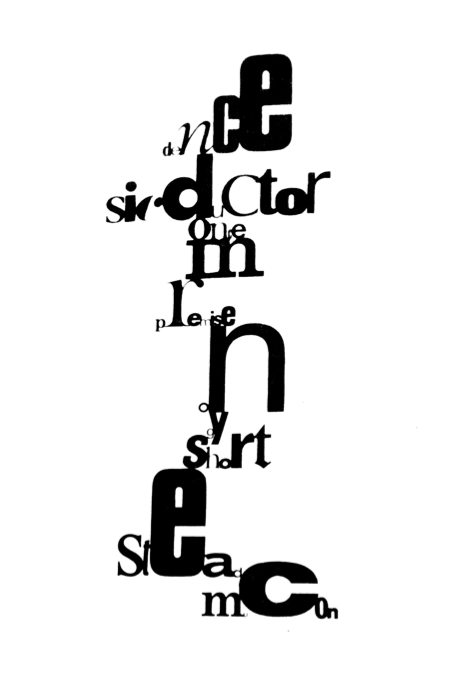

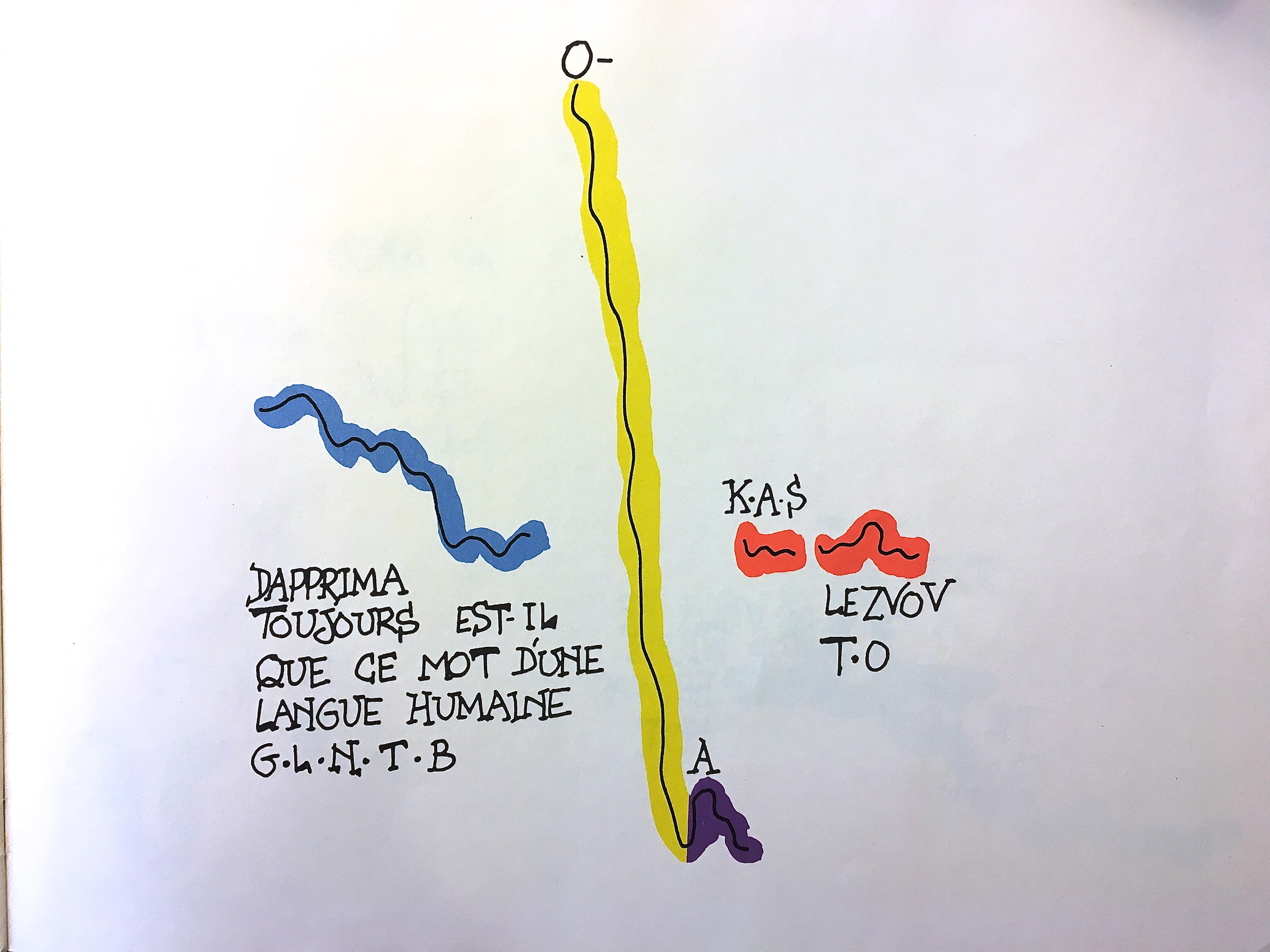

Further complicating the matter is the possible pitch-range of the piece. Cage states: "The notation represents…time vertically, roughly suggested rather than accurately described." [24] If we're assuming the height of the page represents the range of a person's voice stretched to its extremes, then this notation:

Aria, p. 18

It means that the singer needs complete control over her voice to jump from register to register the way Cage intended. This is closer to the classic notion of virtuosity, although Cage milks it for all it's worth.

Finally, it's worth mentioning that Cage, like in Solo for Voice 1, wants the singer to create noises through " 'unmusical' use of the voice". [25] This is represented in the score by black squares which dot the bottom of the page:

Aria, p. 9

Though Cage also allows for these sounds to be made using percussion or mechanical or electronic devices [26], if we assume a performer uses only her voice, then quick transitions between vocal styles are made even more difficult because of the taxing vocal techniques a performer may use to be as unmusical as possible. [27]

6. Song Books (1970)

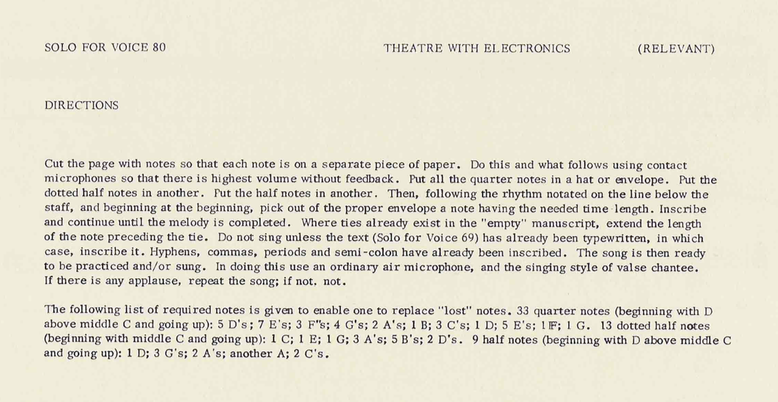

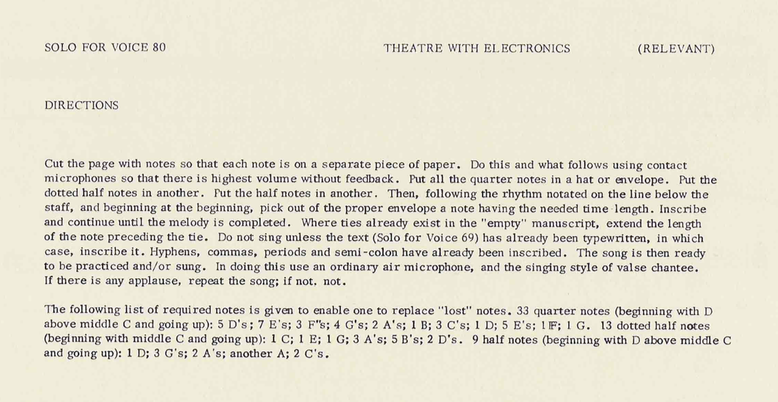

In a list of works that challenge the conventions of vocal virtuosity, Song Books takes the cake. This two-volume set of 91 vocal pieces runs the gamut of vocal possibilities. In fact, it includes techniques found in previous works on this list: Solo for Voice 59 uses notation identical to that of Solo for Voice 1 (no surprise, there, given the titles); Solo for Voice 52 is subtitled "(Aria No. 2)" and uses notation identical to Aria; Solo for Voice 49 asks a performer to simultaneously sing and tap out a rhythm with his fingers like A Chant With Claps; and Solo for Voice 6 requires a performer to translate numbers into actions, similarly to One12. Beyond that, however, lies an even wider spectrum of techniques and notations: inward singing in nos. 22 and 79, microtonal ragas in no. 58, singing at the highest possible volume in no. 64, extreme pitch range in no. 67, senza vibrato in no. 91, extreme glissandi in no. 21 and many others, and what can only be described as sight-singing on steroids in no. 80: [28]Song Books, Vol. II, p. 277

In any given performance of Song Books, a singer many perform many of these pieces back to back, requiring the ability to turn on and off each of these techniques; virtuosity, indeed.

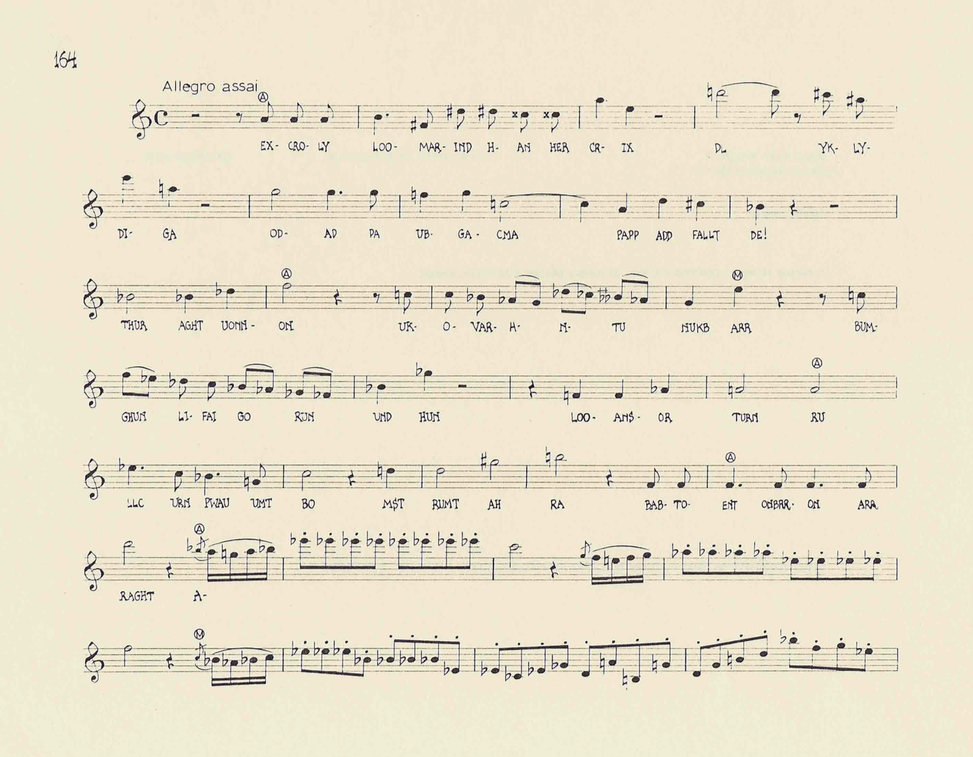

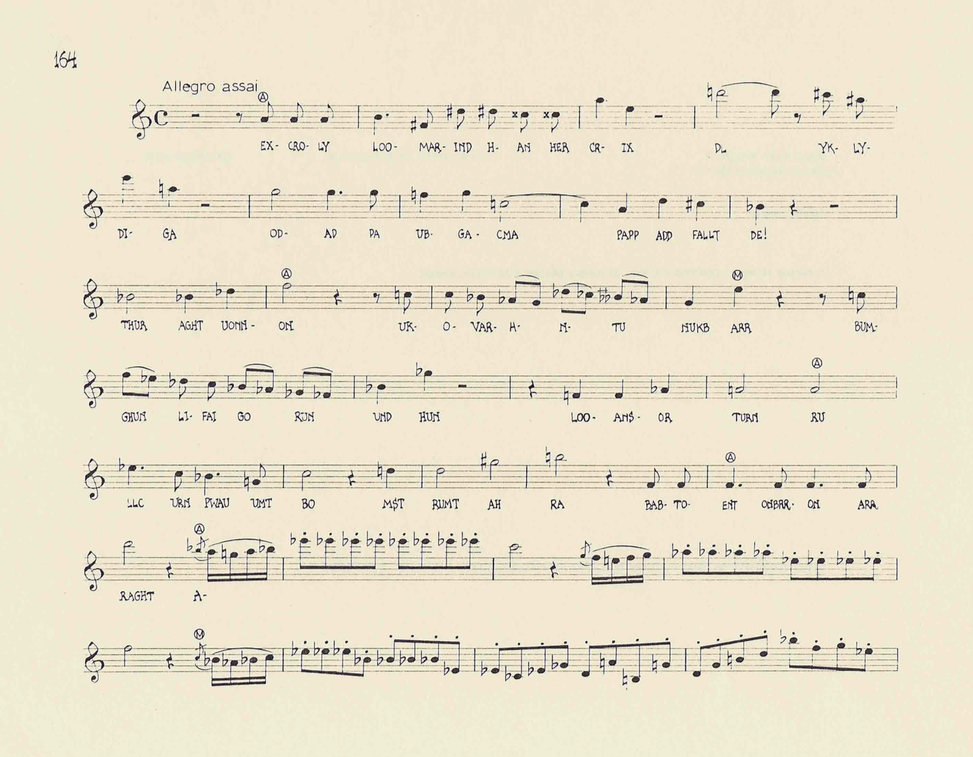

What's more is that in many of these pieces, the singer is accompanied by electronics which manipulate the singer's voice. Take, for example, Solo for Voice 46:

Song Books, Vol. I, p. 164

A straightforward melody is complicated by changes in amplification volume and electronic modulation of an indeterminate parameter at points marked with the letters "A" and "M" in circles, respectively. The bottom system displays a tricky melody. Now imagine having to sing that while listening to the playback of yourself modified in some way, let's say a delay effect. You'd be singing harmony with yourself, and not even necessarily in time. Or let's say the amplitude was increased to a deafening level by the person controlling the electronics (assuming someone else was performing this with you, as is often the case) and you couldn't hear yourself anymore, but still had to sing the piece. The level of muscle memory required to perform the piece and not sound like a screaming concert-goer would be astounding. For all these reasons, Song Books is the quintessential piece in Cage's redefining of virtuosity.

1 See: 4′33″.

2 And as a premature retort: You didn't, and no, you couldn't have.

3 Cage, John, Solo For Voice 1 (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1960), 3.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 "One12," John Cage Complete Works. Accessed May 8, 2017. http://johncage.org/pp/John-Cage-Work-Detail.cfm?w...

8 And from my own experience making the above video, I can confirm how difficult it is to maintain clarity and precision under the circumstances.

9 Cage, John, Sixty-two Mesostics re Merce Cunningham (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1971).

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 The piece is quite difficult to perform, and if you don't believe me, give it a shot. Note how the vocalist in the video above holds out the D in measure 15 for longer than notated. But I won't nitpick here. (Though, if you're going to record a whole album of Cage works, you might as well perform them correctly.)

13 Oh, and yes, pun intended.

14 In fact, much of Cage's vocal work calls attention to the materials themselves rather than the voices producing them. Remember that Cage, a follower of Zen Buddhist practices, wanted to remove the ego from his music on two fronts: his own from his compositions and that of the performers from their realizations of his work.

15 Nor does he ask for a refined hand-clapping technique. And if someone could show me what that is, I'd be most interested.

16 In a sense, that's what a lot of modern musical-theatre and operatic performance practice is. Consider the performers' ability to hit their blocking, act, and dance, all while singing perfectly. In the case of ACWC, this notion has been boiled down to two simple actions: singing and clapping.

17 Cage, John, Sixty-two Mesostics re Merce Cunningham (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1971).

18 Cage, John, Aria (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1960).

19 Italian, French, and English being standard languages in the vocal repertoire.

20 "Aria," John Cage Complete Works. Accessed May 8, 2017. http://johncage.org/pp/John-Cage-Work-

Detail.cfm?work_ID=29

21 It was 1959; forgive her.

22 Cage, John, Aria.

23 In my first performance of the piece in 2008, I chose the following vocal styles: panicked (with whispering); Maya Rudolph impersonating Donatella Versace; a very nasal, high-pitched boy; an excited Italian immigrant; idle boat motor; forte operatic; perfect and calm over-enunciation; legato martial arts commands; slurred and airy folk singing; and Scooby Doo's voice cracking.

24 Cage, John, Aria (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1960).

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 In my second realization of this piece in 2011, I chose the following sounds/actions through chance operations: two metal pots banging like cymbals, a scream, applause, induce vomiting, short crying sound, laughter, throw a tennis ball against the ground, sit down (perform the rest of the piece from the ground), gunshot (cap gun), crack a piece of wood, run offstage and reappear on the opposite side, take off all clothing, exhale audibly, and "Bzzzzz".

28 Cage, John, Song Books, Volumes I & II (New York, NY: Henmar Press Inc., 1970).

* * *

Justin Friello is a singer/actor/composer/multi-instrumentalist from Schenectady, NY. Since 2006, he has been writing text settings for each of E. E. Cummings' published poems. Thus far, he's written close to 300 works for a variety of ensembles featuring voice. Justin is also a singer-songwriter whose most recent solo album, Jack & Jill, was released in August 2016. For more information and recordings, visit: justinfriello.com, justinfriello.bandcamp.com, facebook.com/justinfriellomusic, and youtube.com/justinfriello.

Make sure to subscribe to the FloVoice Newsletter to never miss a note!

Related Content

Quorum Tops A Talented Field

Quorum Tops A Talented FieldJul 10, 2022

Music City Wins it All

Music City Wins it AllJul 9, 2022

Stage is Set for Quartet Finals

Stage is Set for Quartet FinalsJul 8, 2022

Clementones Squeeze in a Varsity Win

Clementones Squeeze in a Varsity WinJul 7, 2022

Highlights from NextGen Varsity Contest

Highlights from NextGen Varsity ContestJul 7, 2022

Top 20 Quartets Named at BHS Charlotte

Top 20 Quartets Named at BHS CharlotteJul 6, 2022

BHS Call Off - Top 20 Quartets

BHS Call Off - Top 20 QuartetsJul 6, 2022

A Historic Kick Off in Charlotte

A Historic Kick Off in CharlotteJul 6, 2022

BHS Charlotte - Day 1

BHS Charlotte - Day 1Jul 6, 2022